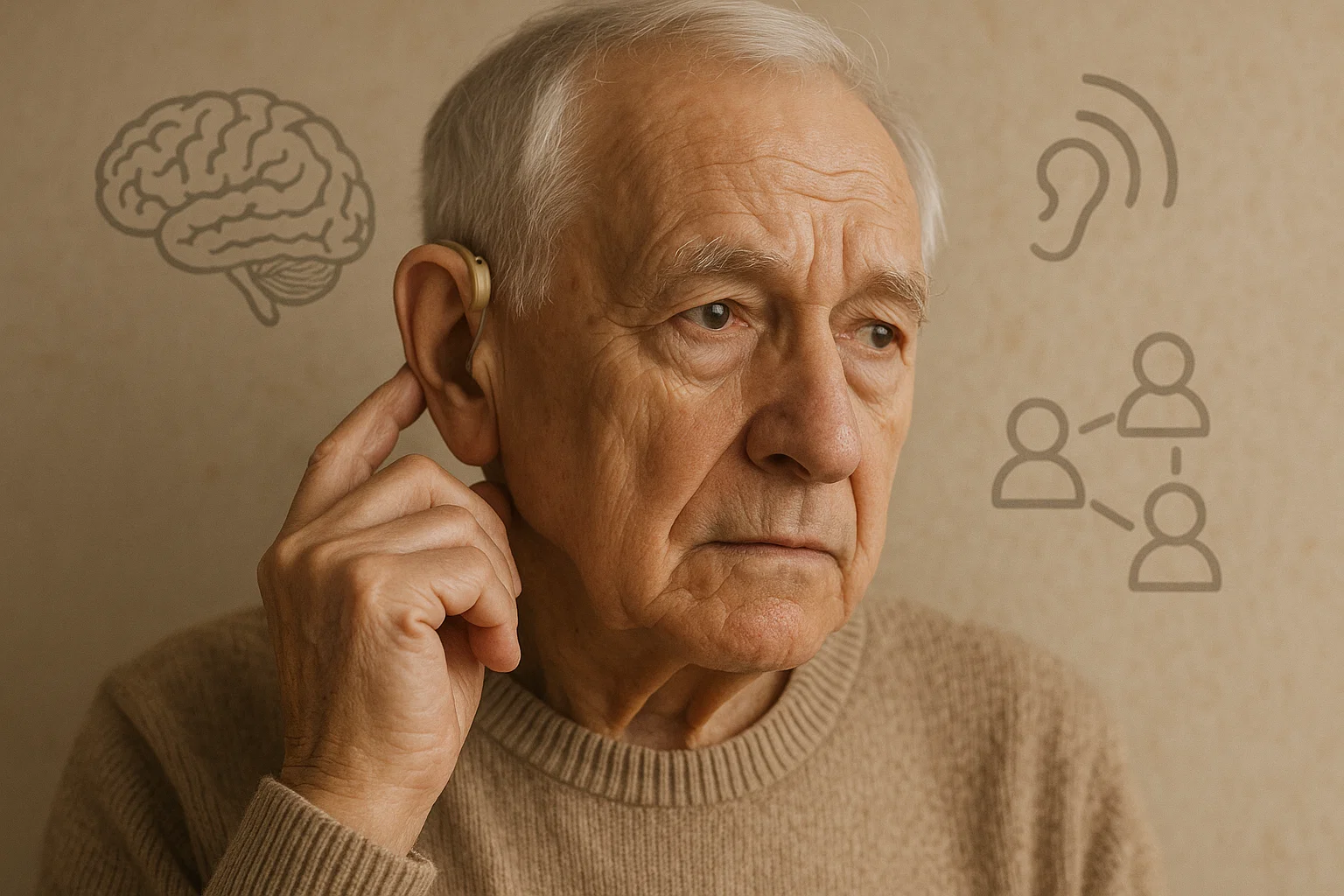

Hearing loss is a common condition affecting millions of older adults worldwide, and it’s increasingly linked to declines in cognitive abilities such as memory and executive function. But not everyone with hearing loss experiences the same degree of cognitive decline. New research from a large European longitudinal study sheds light on why revealing that social factors like isolation and loneliness play a crucial role in moderating this relationship.

This blog explains these findings in everyday terms, highlighting the importance of addressing both hearing impairment and social disconnection to promote cognitive health in later life.

The Growing Concern of Hearing Loss and Cognitive Decline

According to the World Health Organization, approximately 65% of adults aged 60 and above experience some degree of hearing loss, with many suffering moderate to severe impairment. Research has shown that hearing loss is associated with an increased risk of dementia and accelerated cognitive aging. However, this link varies across individuals, suggesting other factors influence cognitive outcomes.

Understanding these factors is vital for developing interventions to maintain mental function in aging populations.

Distinguishing Social Isolation and Loneliness

Social isolation and loneliness are often conflated but represent different experiences:

Social isolation is an objective state where a person has few or no social contacts or interactions.

Loneliness is the subjective feeling of being alone or disconnected, regardless of actual social contact.

Both increase with age due to life changes such as retirement, loss of loved ones, and mobility limitations. Studies indicate that social isolation affects about 22–25% of older adults in Europe and the US, while loneliness varies from 6.5% to 24.2%.

Both conditions have been linked to poorer mental and physical health, including cognitive decline.

A Four-Profile Framework: Beyond Simple Labels

Rather than examining social isolation and loneliness independently, the study adopts a nuanced four-profile framework to capture real-world social experiences:

Non isolated and not lonely socially connected and content

Non isolated but lonely socially connected yet feeling lonely

Isolated but not lonely objectively isolated but without feelings of loneliness

Isolated and lonely socially isolated and feeling lonely

This framework allows for a better understanding of how combinations of objective and subjective social disconnection affect cognition.

Key Findings: Hearing Loss, Social Profiles, and Cognitive Aging

Using data from over 33,000 adults aged 50+ across 12 European countries over 18 years, researchers tracked hearing ability, social profiles, and cognitive performance in episodic memory and executive function.

Hearing Impairment Predicts Cognitive Decline

Older adults with worse hearing consistently scored lower on memory and verbal fluency tests.

Cognitive decline accelerated as hearing impairment became more severe.

Social Isolation and Loneliness Independently Relate to Poorer Cognition

Participants classified as socially isolated and/or lonely showed lower cognitive scores than those socially connected and content.

The “isolated and lonely” group performed the worst across all cognitive domains.

The “Lonely in the Crowd” Are Especially Vulnerable:

Those who were socially connected but still felt lonely experienced a stronger negative impact of hearing loss on memory decline compared to the socially connected and not lonely group.

This suggests loneliness exacerbates cognitive decline even when social networks exist.

Differences Across Cognitive Domains

The moderating effects of social isolation and loneliness were most pronounced for episodic memory (immediate and delayed recall).

Executive function (verbal fluency) also declined with hearing loss but was less affected by social profiles.

Why Does This Matter?

The findings highlight that hearing impairment does not operate in isolation but interacts with psychosocial factors to influence cognitive aging. Specifically:

Loneliness may increase the cognitive burden associated with hearing loss by amplifying stress and reducing mental stimulation.

Social isolation combined with loneliness presents compounded risks, necessitating targeted interventions.

Implications for Healthy Aging

To promote cognitive health in older adults, comprehensive approaches are needed:

Early detection and correction of hearing loss: Use of hearing aids or other assistive technologies to reduce sensory deprivation.

Addressing loneliness: Mental health support, counseling, and community programs to improve subjective feelings of social connection.

Reducing social isolation: Encouraging active social participation and facilitating access to social networks.

Public health policies should integrate sensory and social health interventions, particularly for vulnerable groups like the lonely in the crowd and the isolated and lonely.

Conclusion

This pioneering study reveals the complex interplay between hearing loss, social isolation, loneliness, and cognitive decline. While hearing impairment independently predicts cognitive deterioration, the social context especially loneliness modifies the strength of this relationship.

For individuals and caregivers, awareness of these interacting factors can guide proactive measures to preserve mental function and quality of life in aging. For researchers and policymakers, the findings underscore the necessity of multifaceted strategies that combine sensory health with psychosocial wellbeing to combat cognitive aging effectively.

Reference and Resource

World Health Organization. (2021). Deafness and hearing loss. WHO Fact sheet

Lampraki, C., Zuber, S., Turoman, N., et al. (2025). Profiles of social isolation and loneliness as moderators of the longitudinal association between uncorrected hearing impairment and cognitive aging. Communications Psychology, 3(101). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-025-00277-8